Trauma and healing, two words typically applied to humans or groups of humans, are here used to describe a city. To fully appreciate the efficacy of this linguistic shift, one that we often make without even thinking, we must consider the city holistically as a system.

In my ten-plus years as a policy advisor in urban development in Dubai, that’s precisely what I aimed to achieve: providing decision-makers with a comprehensive perspective of the city by applying the concept of urban metabolism. This concept, initially formulated by academics, remains underutilized by practitioners. In simple terms, the idea is to view the city as a living organism, with the objective of enhancing its metabolism by addressing three elements:

- The flow of materials (inputs and outputs).

- The shape of the city (urban planning).

- The processes and behaviors of the machines and people that constitute and transform its urban fabric.

Like the concept of metabolism that originated in biology, the widely recognized concept of resilience has traversed various fields, spanning from the hard sciences (physics) to the humanities, and ultimately to urban studies:

- In physics, resilience refers to the capacity of a material to absorb shocks or stresses and, after deformation, to elastically return to its original shape.

- For individuals or groups, psychological resilience denotes the ability to, mentally and emotionally, cope with a trauma or a crisis and swiftly return to a pre-existing state.

- In the realm of urban studies, resilient cities are those with the ability to absorb and recover from shocks and stresses, while also preparing for future challenges, be they economic, environmental, social, institutional, or catastrophic events.

The underlying theme of this panel, “Healing after a trauma,” directly relates to both urban and psychological resilience. In this widely disseminated sentence, “after the trauma” the word “trauma” is the key focus. Beirut and its inhabitants do not suffer from trauma, but by its plural emphatic form “traumata”. In my last book “Subsidence” I call this experience “a sedimentation of dramas” (une sédimentations des drames), a situation where, year after year, a new trauma pushes down previous ones.

After the trauma; now the other word, “After”. Well, there is no “after”, as long as…

- the men (because they are mostly men) responsible for the most brilliant heist in the history of banking,

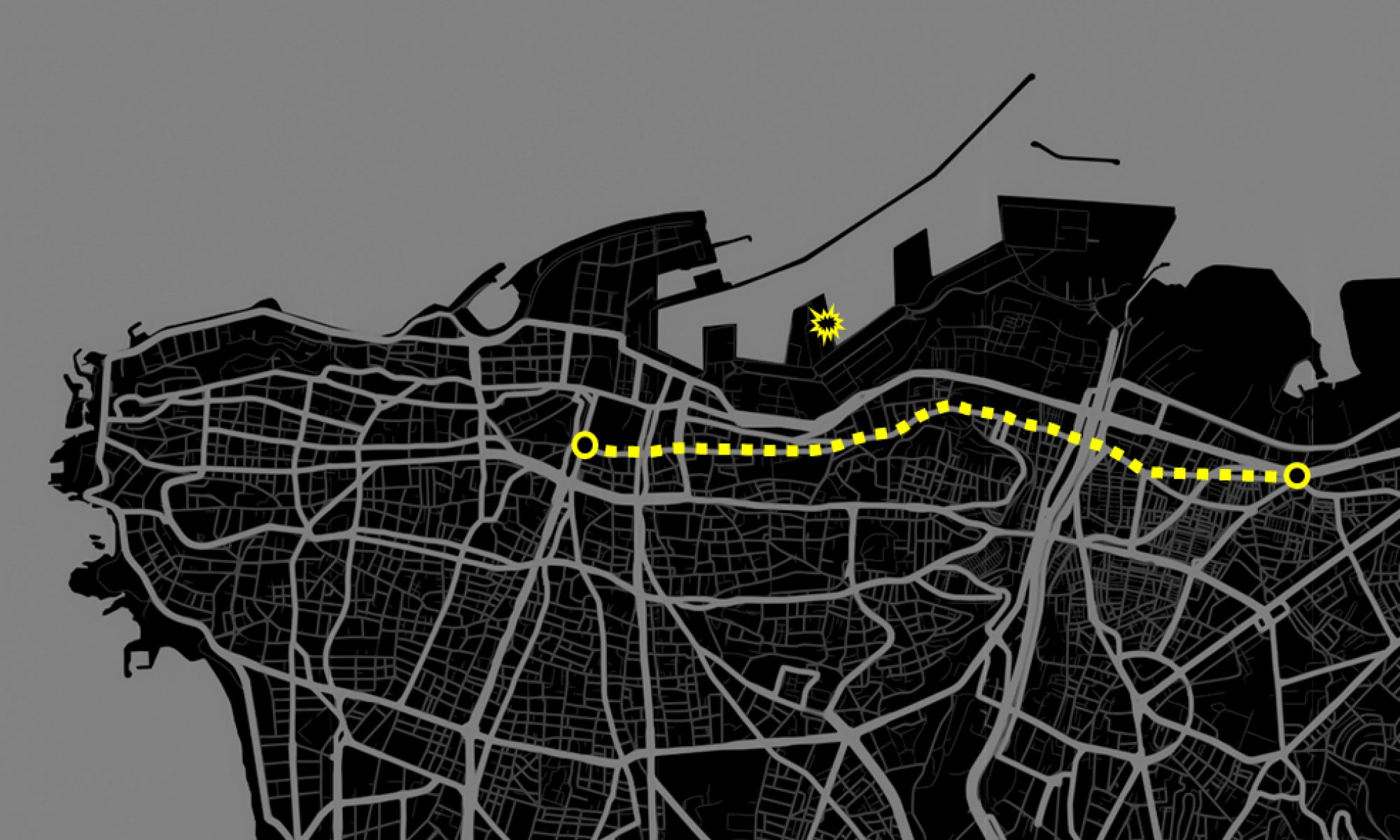

- the men whose actions, inaction, or incompetence, led to one of the largest non-nuclear explosion in history,

- the men responsible for an economic crisis characterized by the World Bank as one of the three worst global crises since the 19th century,

- the men who are currently, as we speak, pushing the city (and the country) to the brink of war and total destruction,

As long as these individuals continue to hold office, retain the capacity to influence decisions, or, more frequently, obstruct them, any attempt to discuss the potential for healing, whether on a human or urban level, remains an inherently absurd endeavor.

Also,

- when the geographical center of the city transforms into a deserted periphery,

- when public services and utilities, such as water and electricity, have completely failed,

- when the entire city relies on diesel and fuel oil, among the most polluting fuels, resulting in alarming air pollution levels that silently kill hundreds of citizens,

- when Beirut’s urban metabolism is in a terminal condition,

- when a modest urban intervention, such as a small piazza, becomes infeasible due to the entrenched forces of inertia within the city,

- when the urban fabric cannot regenerate itself or prepare for future shocks and stresses, hindered by factors like corruption, clientelism, and financial urbanism,

In such circumstances, the discussion of resilience, be it human or urban, becomes an impossible challenge.

I could continue enumerating further examples… perhaps one day I would… but this exercise would undoubtedly be disheartening.

In the current dire situation, the word “after” in “after the trauma” should be replaced by “during,” and the word “trauma” should be substituted with its emphatic plural, “traumata”.

“During multiple traumata” this is the reality that Beirut and its residents are facing today. In this situation, resilience is unattainable, and the initiation of a healing process remains out of reach.

In my view, there has been a pivotal moment in the age-old myth of Beirut’s resilience, the city that has been destroyed seven times and rebuilt seven times, much like its legendary phoenix, which has, each time, stubbornly risen from its ashes. These narratives ceased to be effective after August 4, 2020, when on social networks and in various conversations, we began to encounter sentences such as, “No, we are not okay,” “We are not phoenixes,” “We are not resilient.”

Acceptance of suboptimal temporary solutions with significant negative externalities. That’s where Beirut and Beirutis are today. And this is not resilience, this is not healing.

As a policy advisor in sustainable urban development, I employ the metaphor of urban metabolism to approach urban challenges within a holistic and interconnected system, mirroring the functionality of a living organism.

And the city, as an inherently human construct, serves as a compelling subject for literature to explore questions of human identity and our contemporary zeitgeist. It encapsulates the full spectrum of our contradictions, varied lifestyles, profound existential inquiries, crises, fears, bold innovations, great accomplishments, and most miserable failures.

Fiction, in this context, is a powerful tool to read the urban fabric as we read a literary text to make sense of the city and try to create a language that describes the layers and complexities of urban issues.

That’s what I tried to do in my most recent publication that aligns well with the theme of our discussion. Titled “Subsidence” this term originates from the field of geology and describes a downward vertical sinking movement of the Earth’s surface. This sinking movement can be caused by both natural processes and human activities.

When geological subsidence occurs in urban areas, its immediate consequences often manifest as “sinking cities.” This phenomenon, witnessed in locations ranging from Jakarta to California, results in structural damage to critical infrastructure like water management networks, utilities, buildings, roads, and highways.

Beirut is not directly threatened by geological subsidence due to its rocky terrain. Nevertheless, metaphorically speaking, Beirut has been sinking for several decades, and its infrastructure and utilities have suffered significant damage as a result of this non-geological subsidence.

Therefore, in this booklet, I propose the idea of transferring this term from the realm of geology into the domains of humanities and urban studies, so it can be employed to characterize scenarios where resilience becomes unattainable. Subsidence, consequently, represents the opposite of resilience.

And, as we examine the deteriorated infrastructures and utilities in Beirut, along with some of its striking abandoned buildings like the Holiday Inn, the Murr Tower, or, more recently, the Port Silos, and when we contemplate the city in its entirety, we could be witnessing the consequences of a subsidence.

However, in this context, subsidence is not a geological manifestation; rather, Beirut’s subsidence is a complex interplay of political, social, economic, societal, and psychological factors—in a single word, it is fundamentally human.

THE POLITICS OF TRAUMA AND COLLECTIVE HEALING

PANEL 1: FROM BROKEN CITIES TO URBAN HEALING

TAKminds intervention at the Charles Corm Foundation 13.10.2023